Pancreatic Enzyme Testing for Acute Pancreatitis - CAM 198

Description

Pancreatitis is an inflammation of pancreatic tissue and can be either acute or chronic. Pancreatic enzymes, including amylase, lipase, and trypsinogen can be used to monitor the relative health of the pancreatic tissue. Damage to the pancreatic tissue, including pancreatitis, can result in elevated pancreatic enzyme concentrations whereas depressed enzyme levels are associated with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (P. A. Banks et al., 2013; Stevens & Conwell, 2024).

Regulatory Status

Amylase

The FDA has approved multiple tests for human serum total amylase as well as for pancreatic amylase. FDA Device database accessed on 5/30/2018 yielded 141 records for amylase test.

Lipase

The FDA has approved multiple tests for human serum lipase. FDA Device database accessed on May 30, 2018, yielded 51 records for lipase test.

Trypsinogen/Trypsin/TAP

Trypsin immunostaining, trypsinogen-2 dipstick, and TAP serum tests are considered laboratory developed tests (LDT); developed, validated and performed by individual laboratories.

LDTs are regulated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as high-complexity tests under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA’88).

As an LDT, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved or cleared this test; however, FDA clearance or approval is not currently required for clinical use.

CRP

The FDA has approved multiple tests for human CRP, including assays for conventional CRP, high sensitivity CRP (hsCRP), and cardiac CRP (cCRP). On Sept. 22, 2005, the FDA issued guidelines concerning the assessment of CRP (FDA, 2005).

Procalcitonin

On April 18, 2017, the FDA approved the Diazyme Procalcitonin PCT Assay, Diazyme Procalcitonin Calibrator Set, and Diazyme Procalcitonin Control Set as substantially equivalent and has received FDA 510K clearance for marketing.

IL-6/IL-8

IL-6 and IL-8 are ELISA-based tests and are considered laboratory developed tests (LDT); developed, validated and performed by individual laboratories. IL-6 and IL-8 can also be components of a cytokine panel test, which is also an LDT.

LDTs are regulated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as high-complexity tests under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA’88).

As an LDT, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved or cleared this test; however, FDA clearance or approval is not currently required for clinical use.

Policy

Application of coverage criteria is dependent upon an individual’s benefit coverage at the time of the request.

- For individuals presenting with signs and symptoms of acute pancreatitis (see Note 1), measurement of either serum lipase (preferred) or amylase concentration is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- Measurement of serum lipase and/or amylase concentration is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY in any of the following situations:

- For individuals with an established diagnosis of acute or chronic pancreatitis.

- More than once per visit.

- For asymptomatic individuals during a general exam without abnormal findings.

- For the diagnosis, assessment, prognosis, and/or determination of severity of acute pancreatitis, measurement of serum or urine trypsin/trypsinogen/TAP (trypsinogen activation peptide) is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

The following does not meet coverage criteria due to a lack of available published scientific literature confirming that the test(s) is/are required and beneficial for the diagnosis and treatment of an individual’s illness.

- For the diagnosis, assessment, prognosis, and/or determination of severity of acute pancreatitis, measurement of the following biomarkers is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY:

- C-Reactive Protein (CRP)

- Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

- Interleukin-8 (IL-8)

- Procalcitonin

- For individuals presenting with signs and symptoms of acute pancreatitis (see Note 1), measurement of urinary amylase concentration for the initial diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- For all other situations or conditions not described above, measurement of serum lipase and/or amylase is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

NOTES:

Note 1: Signs and symptoms of acute pancreatitis (Gapp et al., 2023; NIDDK, 2017):

- Mild to severe epigastric pain that begins slowly or suddenly (may spread to the back in some patients)

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Tender to palpitation of epigastrium

- Abdominal distention

- Hypoactive bowel sounds

- Fever

- Rapid pulse

- Tachypnea

- Hypoxemia

- Hypotension

- Anorexia

- Diarrhea

- Cullen sign

- Grey Turner sign

Table of Terminology

| Term |

Definition |

| AACC |

American Association for Clinical Chemistry |

| ABIM |

American Board of Internal Medicine |

| ACCR |

Amylase-to-creatinine clearance ratio |

| ACG |

American College of Gastroenterology |

| AED |

Academy For Eating Disorders |

| AGA |

American Gastroenterological Association |

| AP |

Acute pancreatitis |

| APA |

American Pancreatic Association |

| APA |

American Psychiatric Association |

| APACHE-II |

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation |

| ASCP |

American Society for Clinical Pathology |

| AUCs |

Area under the curve |

| BISAP |

Bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis |

| BUN |

Blood urea nitrogen |

| CADTH |

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health |

| cCRP |

Cardiac C-reactive protein |

| CECT |

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography |

| CLIA ’88 |

Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 |

| CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

| CP |

Chronic pancreatitis |

| CPEC |

Clinical Practice and Economics Committee |

| CRP |

C-reactive protein |

| CT |

Computed axial tomography |

| CTSI |

Computed axial tomography severity index |

| ED |

Eating disorder |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunoassay |

| EPI |

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency |

| ERCP |

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography |

| EUS |

Endoscopic ultrasonography |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

| GRADE |

Grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation |

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HMGB1 |

High Mobility Group Box 1 |

| hsCRP |

High sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| HSROC |

Hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristics curve |

| IAP |

International Association of Pancreatology |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 |

Interleukin-8 |

| LCDs |

Local Coverage Determinations |

| LDH |

Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LDTs |

Laboratory-developed tests |

| MODS |

Multiorgan dysfunction syndrome |

| MRCP |

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NASPGHAN |

North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Pancreas Committee |

| NCDs |

National Coverage Determinations |

| PBMCs |

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PCT |

Procalcitonin |

| PICU |

Pediatric intensive care unit |

| POC |

Point of care |

| RIA |

Radioimmunoassay |

| SIRS |

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome |

| s-isoform |

Salivary glands |

| SPINK1 |

Serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 |

| TAP |

Trypsinogen activation peptide |

| ULN |

Upper limit of normal |

| URL |

Upper limit of reference interval |

| UTDT |

Urine trypsinogen dipstick test |

Rationale

Acute Pancreatitis

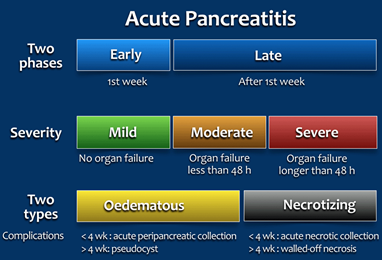

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is inflammation of the pancreatic tissue that can range considerably in clinical manifestations. In approximately 80% of individuals, AP clears up completely or shows significant improvement within one to two weeks. However, it can sometimes lead to serious complications and as such, is often treated in a hospital (informedhealth.org, 2021). Due to the lack of consensus in diagnosing, characterizing, and treating AP, an international group of researchers and practitioners convened in Atlanta in 1992 to write a clinically based classification system for AP, which is now commonly referred to as the Atlanta convention or Atlanta classification system (Bradley, 1993). The Atlanta classification system was then revised in 2012 (Banks et al., 2013). For the diagnosis of AP, two of the three following criteria must be present: “(1) abdominal pain consistent with acute pancreatitis (acute onset of a persistent, severe, epigastric pain often radiating to the back); (2) serum lipase activity (or amylase activity) at least three times greater than the upper limit of normal; and (3) characteristic findings of acute pancreatitis on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) and less commonly magnetic resonance imaging (Toouli et al.) or transabdominal ultrasonography” (italics emphasized by the manuscript’s authors) (Banks et al., 2013). This two-of-three criterion is recommended for diagnostic use by several professional societies (Banks & Freeman, 2006; IAP/APA Working Group, 2013; Tenner et al., 2013). AP can be characterized by two temporal phases, early or late, with degrees of severity ranging from mild (with no organ failure) to moderate (organ failure less than 48 hours) to severe (where persistent organ failure has occurred for more than 48 hours). The two subclasses of AP are edematous AP and necrotizing AP. Edematous AP is due to inflammatory edema with relative homogeneity whereas necrotizing AP displays necrosis of pancreatic and/or peripancreatic tissues (Banks et al., 2013). The figure below from Bollen et al. (2015) outlines the revised Atlanta classification system of AP:

Chronic Pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis (ASCP) is also an inflammation of the pancreatic tissue. The two hallmarks of CP are severe abdominal pain and pancreatic insufficiency (Freedman & Forsmark, 2024). Alcohol-induced chronic pancreatitis (or alcohol pancreatitis) accounts for approximately 40-70% of all cases of CP (Klochkov et al., 2023)

The endocrine system is comprised of several glands which secrete hormones directly into the bloodstream to regulate many different bodily functions. On the other hand, the exocrine system is comprised of glands which secrete products through ducts, rather than directly into the bloodstream. CP affects both the endocrine and exocrine functions of the pancreas. Fibrogenesis occurs within the pancreatic tissue due to activation of pancreatic stellate cells by toxins (for example, those from chronic alcohol consumption) or cytokines from necroinflammation. Measuring the serum levels of amylase, lipase, and/or trypsinogen is not helpful in diagnosing CP since not every CP patient experiences acute episodes, the relative serum concentrations may be either decreased or unaffected, and the sensitivities of the tests are not enough to distinguish reduced enzyme levels (Witt et al., 2007). The best method to diagnose CP is to histologically analyze a pancreatic biopsy, but this invasive procedure is not always the most practical so “contrast-enhanced computed tomography is the best imaging modality for diagnosis. Computed tomography may be inconclusive in early stages of the disease, so other modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, or endoscopic ultrasonography with or without biopsy may be used” (Barry, 2018). Previously, ERCP was commonly used to diagnose CP, but the procedure can cause post-ERCP pancreatitis. Genetic factors are also implicated in CP, especially those related to trypsin activity, the serine protease inhibitor SPINK1, and cystic fibrosis (Borowitz et al., 1995; Patel, 2017; Witt et al., 2007).

Amylase

Amylase is an enzyme produced predominantly in the salivary glands (s-isoform) and the pancreas (p-isoform or p-isoamylase) and is responsible for the digestion of polysaccharides, cleaving at the internal 1→4 alpha linkage. Up to 60% of the total serum amylase can be of the s-isoform. The concentration of total serum amylase as well as the pancreatic isoenzyme increase following pancreatic injury or inflammation (Basnayake & Ratnam, 2015; Vege, 2024a). Even though the serum concentration of the pancreatic diagnostic enzymes, including amylase, lipase, elastase, and immunoreactive trypsin all increase within 24 hours of onset of symptomology, amylase is the first pancreatic enzyme to return to normal levels so the timing of testing is of considerable importance for diagnostic value (Basnayake & Ratnam, 2015; Ventrucci et al., 1987; Yadav et al., 2002). The half-life of amylase is 12 hours since it is excreted by the kidneys, so its clinical value decreases considerably after initial onset of AP. The etiology of the condition can also affect the relative serum amylase concentration. In up to 50% of AP instances due to hypertriglyceridemia (high blood levels of triglycerides), the serum amylase concentration falls into the normal range, and normal concentrations of amylase has been reported in cases of alcohol-induced AP (Basnayake & Ratnam, 2015; Quinlan, 2014); in fact, one study shows that 58% of the cases of normoamylasemic AP was associated with alcohol use (Clavien et al., 1989). Elevated serum amylase concentrations also can occur in conditions other than AP, including hyperamylasemia (excess amylase in the blood) due to drug exposure (Ceylan et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016), bulimia nervosa (Wolfe et al., 2011), leptospirosis (Herrmann-Storck et al., 2010), and macroamylasemia (Vege, 2024a). Serum amylase levels are often significantly elevated in individuals with bulimia nervosa due to recurrent binge eating episodes (Wolfe et al., 2011).

Macroamylasemia is a condition where the amylase concentration increases due to the formation of macroamylases, complexes of amylase with immunoglobulins and/or polysaccharides. Macroamylasemia is associated with other disease pathologies, “including celiac disease, HIV infection, lymphoma, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and monoclonal gammopathy”. Suspected macroamylasemia in instances of isolated amylase elevation can be confirmed by measuring the amylase-to-creatinine clearance ratio (ACCR) since macroamylase complexes are too large to be adequately filtered. Normal values range from three to four percent with values of less than one percent supporting the diagnosis of macroamylasemia. ACCR itself is not a good indicator of AP since low ACCR is also exhibited in diabetic ketoacidosis and severe burns (Vege, 2024a). Hyperamylasemia is also seen in other extrapancreatic conditions, such as appendicitis, salivary disease, gynecologic disease, extra-pancreatic tumors, and gastrointestinal disease (Terui et al., 2013; Vege, 2024a). Gullo’s Syndrome (or benign pancreatic hyperenzymemia) is a rare condition that also exhibits high serum concentrations of pancreatic enzymes without showing other signs of pancreatitis (Kumar et al., 2016). No correlation has been found between the concentration of serum amylase and the severity or prognosis of AP (Lippi et al., 2012).

Urinary amylase and peritoneal amylase concentrations can also be measured. Rompianesi et al. (2017) reviewed the use of urinary amylase and trypsinogen as compared to serum amylase and serum lipase testing. The authors note that “with regard to urinary amylase, there is no clear-cut level beyond which someone with abdominal pain is considered to have acute pancreatitis”. Three studies regarding urinary amylase were reviewed — each with 134 – 218 participants — and used the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristics curve (HSROC) analysis to compare the accuracy of the studies. Results showed that “the models did not converge” and the authors concluded that “we were therefore unable to formally compare the diagnostic performance of the different tests” (Rompianesi et al., 2017).

Another study investigated the use of peritoneal amylase concentrations for diagnostic measures and discovered that patients with intra-abdominal peritonitis had a mean peritoneal amylase concentration of 816 U/L (142 – 1,746 U/L range), patients with pancreatitis had a mean concentration of 550 U/L (100 – 1,140 U/L range), and patients with other “typical infectious peritonitis” had a mean concentration of 11.1 U/L (0 – 90 U/L range). Conclusions state “that peritoneal fluid amylase levels were helpful in the differential diagnosis of peritonitis in these patients” and that levels > 100 U/L “differentiated those patients with other intra-abdominal causes of peritonitis from those with typical infectious peritonitis” (Burkart et al., 1991). The authors do not state if intraperitoneal amylase is specifically useful in diagnosing AP.

Liu et al. (2021) conducted a retrospective cohort study to evaluate whether serum amylase and lipase could serve as a biomarker to predict pancreatic injury in 79 critically ill children who died of different causes. Through autopsy investigation, the subjects were divided into pancreatic injury group and non-pancreatic injury group. Forty-one patients (51.9%) exhibited pathological changes of pancreatic injury. Levels of lactate, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, and troponin-I in the pancreatic injury group were significantly higher than that in the noninjury group. "Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that serum amylase, serum lipase, and septic shock were significantly associated with the occurrence rate of pancreatic injury". Therefore, the authors conclude that "serum amylase and lipase could serve as independent biomarkers to predict pancreatic injury in critically ill children” (Liu et al., 2021).

In a prospective case control study, Judal et al. (2022) investigated urinary amylase levels for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. One major challenge with measurement of serum amylase is its short half-life which returns to normal levels within a short period of time. This study enrolled 100 patients (50 healthy and 50 with acute pancreatitis) who were measured for serum amylase, serum lipase, and urinary amylase. There was a statistically significant increase in the serum amylase, lipase, and urinary amylase mean values of patients with AP. "Serum amylase had the highest sensitivity (100%) and serum lipase had the highest specificity (96.53%). The sensitivity and specificity of urinary amylase was found to be 97.25% and 91.47% respectively" (Judal et al., 2022). The authors conclude that urinary amylase is a convenient and sensitive test for diagnosis.

Ryholt et al. (2024) conducted a retrospective study with data collected throughout 2020 to “assess the utilization of appropriate laboratory testing related to the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.” The authors were particularly interested in the overuse of amylase testing or amylase and lipase testing together when lipase testing alone would have been sufficient for AP diagnosis. Overall, 2567 (9.3%) of all amylase and lipase tests were determined to be unnecessary, an estimated $128,350 in total cost savings if eliminated. Of the unnecessary tests, 1881 (73.2%) were amylase tests and 686 (26.7%) were lipases tests. The authors also note that “an analysis of test-ordering behavior by providers revealed that 81.5% of all unnecessary tests were ordered by MDs.” The authors conclude that the “study demonstrated that amylase and lipase tests have been overutilized in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis” (Ryholt et al., 2024).

Lipase (Pancreatic Lipase or Pancreatic Triacylglycerol Lipase)

Pancreatic lipase or triacylglycerol lipase (herein referred to as “lipase”) is an enzyme responsible for hydrolyzing triglycerides to aid in the digestion of fats. Like amylase, lipase concentration increases shortly after pancreatic injury (within three to six hours). However, contrary to amylase, serum lipase concentrations remain elevated for one to two weeks after initial onset of AP since lipase can be reabsorbed by the kidney tubules (Lippi et al., 2012). Moreover, the pancreatic lipase concentration is 100-fold higher than the concentration of other forms of lipases found in other tissues such as the duodenum and stomach (Basnayake & Ratnam, 2015). Both the sensitivity and the specificity of lipase in laboratory testing of AP are higher than that of amylase (Yadav et al., 2002). A study by Coffey et al. (2013) found “an odds ratio of 7.1 (95% confidence interval 2.5-20.5; P<0.001) for developing severe AP” in patients ages 18 or younger when the serum lipase concentration is at least 7-fold higher than upper limit of normal. However, in general, elevated serum lipase concentration is not used to determine the severity or prognosis of AP (Ismail & Bhayana, 2017). Hyperlipasemia can also occur in other conditions such as Gullo’s Syndrome (Kumar et al., 2016). The use of lipase to determine etiology of AP is of debate. A study by Levy et al. (2005) reports that lipase alone cannot be used to determine biliary cause of AP whereas other studies have indicated that a ratio of lipase-to-amylase concentrations ranging from 2:1 to more than 5:1 can be indicative of alcohol-induced AP (Gumaste et al., 1991; Ismail & Bhayana, 2017; Pacheco & Oliveira, 2007; Tenner & Steinberg, 1992).

The review by Ismail and Bhayana (2017) included a summary table (Table 1 below) comparing various studies concerning the use of amylase and lipase for diagnosis of AP as well as a table (Table 2 below) comparing the cost implication of the elimination of double-testing for AP.

Table 1: Summary of numerous studies comparing lipase against amylase (URL – Upper Limit of Reference interval, AP – Acute Pancreatitis).

| Design and reference |

Participant (patients with abdominal pain/AP) |

Threshold |

Results |

Conclusion |

|

| Serum lipase |

Serum amylase |

||||

| Prospective study [56] |

384/60 |

Two times URL |

Diagnostic accuracy and efficiency are > 95% for both |

No difference between amylase and lipase in diagnosing AP |

|

| Prospective study [57] |

306/48 |

Serum lipase > 208 U/L Serum amylase > 110 U/L |

92% sensitivity 87% specificity 94% Diagnostic accuracy |

93% sensitivity 87% specificity 91% Diagnostic accuracy |

Both tests are associated with AP, but serum lipase is better than amylase |

| Prospective study [58] |

328/51 |

Serum lipase: > 208 U/L (Day 1) > 216 U/L (Day 3) Serum amylase: > 176 U/L > 126 U/L (Day 3) |

Day 1: 64 % Sensitivity 97% Specificity Day 3: 55% Sensitivity 84% Specificity |

Day 1: 45 % Sensitivity 97% Specificity Day 3: 35% Sensitivity 92% Specificity |

Serum lipase is better at diagnosing early and late AP |

| Retrospective study [63] |

17,531/320 *49 had elevated lipase only |

Serum lipase > 208 U/L Serum amylase > 114 U/L |

90.3% Sensitivity 93.6% Specificity |

78.7% Sensitivity 92.6% Specificity |

Serum lipase is more accurate marker for AP |

| Cohort study [2] |

1,520/44 |

Three times URL |

64% Sensitivity 97% Specificity |

50% Sensitivity 99% Specificity |

Serum lipase is preferable to use in comparison to amylase alone or both tests |

| Retrospective study [59] |

3451/34 *33 patients had elevated amylase and 50 had elevated lipase only |

Three or more times URL |

95.5% Sensitivity 99.2% Specificity |

63.6% Sensitivity 99.4% Specificity |

Both enzymes have good accuracy, but lipase is more sensitive than amylase |

| Cohort study [60] |

151/117 *6 patients with gallstone-induced and 5 patients with alcohol-induced AP had elevated lipase only |

Three times URL |

96.6% Sensitivity 99.4% Specificity |

78.6% Sensitivity 99.1% Specificity |

Lipase is more sensitive in diagnosing AP and using it alone would present a substantial cost saving on health care system |

| Prospective study [61] |

476/154 *58 patients had a normal amylase level |

Three times URL |

91% Sensitivity 92% Specificity |

62% Sensitivity 93% Specificity |

Lipase is more sensitive than amylase and should replace amylase in diagnosis of AP |

| Cohort study [62] |

50/42 *8 patients had elevated lipase only |

Three times URL |

100% Sensitivity |

78.6% Sensitivity |

Lipase is a better choice than amylase in diagnosis of AP |

This table is a list of individual studies examining the specificity and sensitive of serum lipase and serum amylase in diagnosing AP. In each of the listed studies except one, the authors concluded that serum lipase is better than serum amylase for AP. The only outlier used a lower threshold in considering enzyme elevation; in particular, two times the upper limit of reference interval (URL) was used whereas the Atlanta classification system recommends at least three times the URL to determine enzyme elevation (Ismail & Bhayana, 2017).

Table 2: Summary of studies exploring the cost implication associated with eliminating amylase test.

| Design and Reference |

Costs |

Volume of test |

Results |

| Cohort study (UK) [2] |

Amylase costs £1.94 Lipase cost £2.50 |

1383 request for 62 days costing £6136 for both tests |

Testing lipase only will result in cost saving |

| Cohort study (UK) [60] |

Single amylase or lipase cost about £0.69 each Cost of both measured together were £0.99. |

2979 requests costing £2949.21 |

Measuring lipase would save health care system an estimate of £893.70 per year |

| Prospective study (US) [71] |

Patients charged $35 for either lipase or amylase |

618 co-ordered both lipase and amylase |

Amylase test was removed from common order sets in the electronic medical record Reduced the co-ordering of lipase and amylase to 294 Overall saving of $135,000 per year |

This table specifically outlines studies that compared the financial cost of the serum amylase and serum lipase tests for diagnosing AP. All three studies show cost savings if only lipase concentration is used. In fact, one study by researchers in Pennsylvania resulted in the removal of the amylase test “from common order sets in the electronic medical record” (Ismail & Bhayana, 2017).

Furey et al. (2020) compared amylase and lipase ordering patterns for patients with AP. A total of 438 individuals were included in this study. The researchers noted that “All patients had at least one lipase ordered during their admission, and only 51 patients (12%) had at least one amylase ordered. On average, lipase was elevated 5 times higher above its respective upper reference limit than amylase at admission” (Furey et al., 2020). Further, patients undergoing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal) were more likely to have amylase ordered. These results showed that in 88% of patients with AP, amylase measurement was not necessary; moreover, “Of patients for whom amylase was ordered, it was common for these patients to be those referred to surgical procedures, possibly because amylase normalization may be documented faster than that of lipase” (Furey et al., 2020).

In a retrospective cross-sectional study by El Halabi et al. (2019), the clinical utility and economic burden of routine serum lipase examination in the emergency department was observed. From 24,133 adult patients admitted within a 12-month period, serum lipase levels were ordered for 4,976 (20.6%) patients. Of those 614 (12.4%) who had abnormal lipase levels, 130 of those patients were above the diagnostic threshold for acute pancreatitis (>3 times the ULN) and 75 patients had confirmed diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. In total, 1,890 patients had normal no abdominal pain or history of acute pancreatitis, but 251 of these patients were tested for lipase levels, leading to a total cost of $51,030. These results triggered unneeded cross-sectional abdominal imaging in 61 patients and unwarranted gastroenterology consultation in three patients, leading to an additional charge of $28,975. The authors conclude that "serum lipase is widely overutilised in the emergency setting resulting in unnecessary expenses and investigations” (El Halabi et al., 2019).

Liu et al. (2021) studied the use of serum amylase and lipase for the prediction of pancreatic injury in critically ill children admitted to the PICU. Seventy-nine children who died from different cases were studied from autopsy and it was found that 41 of these patients had pathological signs of pancreatic injury. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that serum amylase, serum lipase, and septic shock were significantly associated with the occurrence rate of pancreatic injury. Serum amylase was measured with 53.7% sensitivity, 81.6% specificity, cut off value of 97.5, and AUC of 0.731. Serum lipase was measured with 36.6% sensitivity, 92.1% specificity, cut off value of 61.1, and AUC of 0.727. The authors conclude that “serum amylase and lipase could serve as independent biomarkers to predict pancreatic injury in critically ill children” (Liu et al., 2021).

Ritter. J et al. (2019) showed that for individuals with acute pancreatitis experiencing a hospital stay, there was no difference in disease severity between individuals who had repeat lipase and/or amylase testing and those who did not have repeat testing. They found that approximately “one-third of inpatient encounters with at least one elevated amylase or lipase test continued with repeat testing with as many as 25 additional tests after the initial elevated test result. The mean number of unnecessary additional serial tests was 2.8 and 2.4 for amylase and lipase, respectively, consistent with the tests being ordered each hospital day, given a 3-day nationwide average inpatient stay for acute pancreatitis” (Ritter. J et al., 2019). According to their findings, “ambulatory settings had the highest rates of concurrent testing while emergency departments had the lowest” (Ritter. J et al., 2019). While the cost of unnecessary serial and concurrent amylase/lipase tests are relatively small when considering the entire health system, based on their findings, they estimated that the national impact of these two tests could be as much as $5.8 million in variable costs alone. They concluded that unnecessary laboratory testing remains a problem despite evidence-based guidelines and programs that have been designed to reduce and eliminate it (Ritter. J et al., 2019).

Trypsin/Trypsinogen/TAP

Trypsin is a protease produced by the pancreatic acinar cells. Trypsin is first synthesized in its zymogen form, trypsinogen, which has its N-terminus cleaved to form the mature trypsin. Pancreatitis can result in blockage of the release of the proteases while their synthesis continues. This increase in both intracellular trypsinogen and cathepsin B, an enzyme that can cleave the trypsinogen activation peptide (TAP) from the zymogen to form mature trypsin, results in a premature intrapancreatic activation of trypsin. This triggers a release of both trypsin and TAP extracellularly into the serum and surrounding peripancreatic tissue. Due to the proteolytic nature of trypsin, this response can result in degradation of both the pancreatic and peripancreatic tissues (i.e., necrotizing AP) (Vege, 2024c; Yadav et al., 2002). Trypsin activity “is critical for the severity of both acute and chronic pancreatitis” (Zhan et al., 2019). When the intracellular activity of trypsin escalates, an increase is also reflected in the number of pancreatitis cases overall, as well as in the severity of these cases (Sendler & Lerch, 2020).

Since trypsinogen is readily excreted, a urine trypsinogen-2 dipstick test has been developed (Actim Pancreatitis test strip from Medix Biochemica), which has a reported specificity of 85% for severe AP within 24 hours of hospital admission (Lempinen et al., 2001). Another study reported that the trypsinogen-2 dipstick test has a specificity of 95% and a sensitivity of 94% for AP, which is higher than a comparable urine test for amylase (Kemppainen et al., 1997). As of 2023, the FDA has not approved the use of the trypsinogen-2 dipstick test for the detection or diagnosis of AP. The quality control review of the clinical trial is underway in the United States (Eastler, 2023). The use of TAP for either a diagnostic or prognostic tool is of debate (Lippi et al., 2012).

The study by Neoptolemos et al. (2000) reported that a urinary TAP assay had a 73% specificity for AP. However, another study using a serum TAP methodology reported a 23.5% sensitivity and 91.7% specificity for AP and concluded that “TAP is of limited value in assessing the diagnosis and the severity of acute pancreatic damage” (Pezzilli et al., 2004).

Yasuda et al. (2019) completed a multicenter study in Japan which measured the usefulness of the rapid urinary trypsinogen-2 dipstick test and levels of urinary trypsinogen-2 and TAP concentration as prognostic tools for AP. A total of 94 patients participated in this study from 17 medical institutions between April 2009 and December 2012. The researchers determined that “The trypsinogen-2 dipstick test was positive in 57 of 78 patients with acute pancreatitis (sensitivity, 73.1%) and in 6 of 16 patients with abdominal pain but without any evidence of acute pancreatitis (specificity, 62.5%)” (Yasuda et al., 2019). Further, both TAP and urinary trypsinogen-2 levels were significantly higher in patients with extra-pancreatic inflammation. The authors concluded that the urinary trypsinogen-2 dipstick test is a useful tool for AP diagnoses.

Simha et al. (2021) studied the utility of POC urine trypsinogen dipstick test for diagnosing AP in an emergency unit. Urine trypsinogen dipstick test (UTDT) was performed in 187 patients in which 90 patients had AP. UTDT was positive in 61 (67.7%) of the 90 AP patients. In the 97 non pancreatitis cases, UTDT was positive in nine of those cases (9.3%). The sensitivity and specificity of UTDT for acute pancreatitis was 67.8% and 90.7%, respectively. The authors conclude that although it is a great and convenient possibility as a POC test, “the low sensitivity of UTDT could be a concern with its routine use” (Simha et al., 2021).

Other Biochemical Markers (CRP, Procalcitonin, IL-6, IL-8)

Acute pancreatitis results in the activation of the immune system. Specific markers including C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-8 (IL-8) have been linked to AP (Toouli et al., 2002; Vege, 2024b; Yadav et al., 2002). CRP is a nonspecific marker for inflammation that takes 48 – 72 hours to reach maximal concentration after initial onset of AP but is reported to have a specificity of 93% in detecting pancreatic necrosis. CRP can be used in monitoring the severity of AP; however, imaging techniques, including CT, and evaluative tools, such as the APACHE-II (acute physiology and chronic health evaluation) test, are preferred methods (IAP/APA Working Group, 2013; Quinlan, 2014).

Procalcitonin is the inactive precursor of the hormone calcitonin. Like CRP, procalcitonin has been linked to inflammatory responses, especially in response to infections and sepsis. Procalcitonin levels are elevated in AP and are significantly elevated (≥ 3.5 ng/mL for at least two consecutive days) in cases of AP associated with multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (MODS) (Rau et al., 2007). Moreover, the elevated procalcitonin levels decrease upon treatment for AP; “however, further research is needed in order to understand how these biomarkers can help to monitor inflammatory responses in AP” (Simsek et al., 2018).

The concentration of inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 become elevated in AP with a maximal peak within the first 24 hours after initial onset of AP (Yadav et al., 2002). One study by Jakkampudi et al. (2017) shows that IL-6 and IL-8 are released in a time-dependent manner after injury to the pancreatic acinar cells. This, in turn, activated the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), which propagate acinar cell apoptosis that results in further release of cytokines to increase the likelihood of additional cellular damage.

A study conducted by Khanna et al. (2013) compares the use of biochemical markers, such as CRP, IL-6, and procalcitonin, in predicting the severity of AP and necrosis to that of the clinically used evaluative tools, including the Glasgow score and APACHE-II test. Their results indicate that CRP has a sensitivity and specificity of 86.2% and 100%, respectively, for severe AP and a sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 81.4%, respectively, for pancreatic necrosis. These scores are better than those reported for the clinical evaluative tools (see table below). IL-6 also shows an increase in both sensitivity and specificity; however, the values for procalcitonin are considerably lower than either CRP or IL-6 in all parameters (Khanna et al., 2013).

| Data from |

Severe AP |

Pancreatic necrosis |

||

| (Khanna et al., 2013) |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

| Glasgow |

71.0 |

78.0 |

64.7 |

63.6 |

| APACHE-II |

80.6 |

82.9 |

64.7 |

61.8 |

| CRP |

86.2 |

100 |

100 |

81.4 |

| IL-6 |

93.1 |

96.8 |

94.1 |

72.1 |

| Procalcitonin |

86.4 |

75.0 |

78.6 |

53.6 |

Another study by Hagjer and Kumar (2018) compared the efficacy of the bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis (BISAP) scoring system to CRP and procalcitonin shows that CRP is not as accurate for prognostication as BISAP. BISAP has AUCs for predicting severe AP and death of 0.875 and 0.740, respectively, as compared to the scores of CRP (0.755 and 0.693, respectively). Procalcitonin, on the other hand, had values of 0.940 and 0.769 for predicting severe AP and death, respectively. The authors concluded that it “is a promising inflammatory marker with prediction rates similar to BISAP” (Hagjer & Kumar, 2018).

Li et al. (2018) completed a meta-analysis to determine the relationship between high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and AP. HMGB1 protein is a nuclear protein with several different purposes depending on its location (Yang et al., 2015). These researchers analyzed data from 27 different studies comprised of 1908 of participants (896 with mild AP, 700 with severe AP and 312 healthy controls). Overall, serum HMGB1 and IL-6 levels were higher in patients with both severe and mild AP compared to controls; further, and serum HMGB1 and IL-6 levels were significantly higher in patients with severe AP than mild AP (Li et al., 2018). The authors concluded that serum HMGB1 and IL-6 levels “might be used as effective indicators for pancreatic lesions as well as the degree of inflammatory response” and that both HMGB1 and IL-6 are closely correlated with pancreatitis severity.

Tian et al. (2020) studied the diagnostic value of C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT), IL-6, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. A total of 153 patients were divided into the mild acute pancreatitis group (81) and severe pancreatitis group (72). Significant differences in the values of these enzymes were found between both groups. The sensitivity, specificity, and AUC were determined as seen in the chart below. The AUC of combined detection of CRP, PCT, IL-6 and LDH was 0.989. The authors conclude that "the combined detection of CRP, PCT, IL-6 and LDH has a high diagnostic value for judging the severity of acute pancreatitis” (Tian et al., 2020).

| Enzyme |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

AUC |

| CRP |

55.6% |

73% |

0.637 |

| PCT |

77.8% |

94% |

0.929 |

| IL-6 |

80.2% |

85% |

0.886 |

| LDH |

82.7% |

96% |

0.919 |

In a retrospective cohort study, Wei et al. (2022) investigated the predictive value of serum cholinesterase (ChE) in the mortality of acute pancreatitis. A total of 692 patients were enrolled in the study and were divided into the ChE-low group (378 patients) or ChE-normal group (314 patients). Mortality was significantly different in two groups (10.3% in ChE-low vs. 0.0% ChE- normal) and organ failure also differed (46.6% ChE-low vs. 8.6% ChE-normal). The area under the curve of serum ChE was 0.875 and 0.803 for mortality and organ failure, respectively. The authors conclude that "lower level of serum ChE was independently associated with the severity and mortality of AP” (Wei et al., 2022).

International Association of Pancreatology (IAP/APA Working Group) and the American Pancreatic Association (APA)

In 2012, a joint conference between the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP/APA Working Group) and the American Pancreatic Association (APA) convened to address the guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. This conference made their recommendations using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system. The IAP/APA Working Group (2013) are detailed with 38 recommendations covering 12 different topics, ranging from diagnosis to predicting severity of disease to timing of treatments. As concerning the diagnosis and etiology of AP, the associations conclude with “GRADE 1B, strong agreement” that the definition of AP follow the Atlanta classification system where at least two of the following three criteria are evident — the clinical manifestation of upper abdominal pain, the laboratory testing of serum amylase or serum lipase where levels are more than three times the upper limit of normal values, and/or the affirmation of pancreatitis using imaging methods (IAP/APA Working Group, 2013). IAP/APA Working Group (2013) specifically did not include the trypsinogen-2 dipstick test in their recommendations “because of its presumed limited availability”. One question addressed by the committee was the continuation of oral feeding being withheld for patients until the lab serum tests returned within normal values. With a GRADE 2B, strong agreement finding, they conclude that “it is not necessary to wait until pain or laboratory abnormalities completely resolve before restarting oral feeding” (IAP/APA Working Group, 2013). No specific discussion on the preference of either serum amylase or lipase is included within the guidelines as well as no discussion of the use of either serum test beyond initial diagnosis of AP (i.e., no continual testing for disease monitoring is included). Furthermore, no discussion concerning the use of urinary or peritoneal amylase concentrations for AP.

With regards to CRP and/or procalcitonin, the IAP/APA does not address the topic in any detail. As part of IAP/APA Working Group (2013) recommendation (GRADE 2B) concerning the best score or marker to predict the severity of AP, they state “that there are many different predictive scoring systems for acute pancreatitis ..., including single serum markers (C-reactive protein, hematocrit, procalcitonin, blood urea nitrogen), but none of these are clearly superior or inferior to (persistent) SIRS”, which is Systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Moreover, in response to their recommendation for admission to an intensive care unit in AP (GRADE 1C), they state that “the routine use of single markers, such as CRP, hematocrit, BUN or procalcitonin alone to triage patients to an intensive care setting is not recommended” (IAP/APA Working Group, 2013).

American Gastroenterological Association (AGA)

The Clinical Practice and Economics Committee (CPEC) of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute released the AGA Institute Medical Position Statement on Acute Pancreatitis as approved by the AGA Institute Governing Board in 2007 to address differences in the recommendations of various national and international societies concerning AP. Within their recommendations, Baillie (2007) address the necessity of timeliness in the applicability of serum amylase and/or serum lipase testing. Per their recommendations, either serum amylase or serum lipase should be tested within 48 hours of admission. AP is consistent with amylase or lipase levels greater than three times the upper limit of the normal value. Baillie (2007) specifically state that the “elevation of lipase levels is somewhat more specific and is thus preferred”. The AGA guidelines do not address the use of either urinary or peritoneal concentrations of amylase in AP. Also, any patient presenting symptoms of unexplained multiorgan failure or systemic inflammatory response syndrome should be tested for a possible AP diagnosis. Concerning etiology of the phenotype, they suggest that upon admission, “all patients should have serum obtained for measurement of amylase or lipase level, triglyceride level, calcium level, and liver chemistries” (Baillie, 2007). Invasive evaluation, such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), should be avoided for patients with a single occurrence of AP. The only mention of CRP in their guidelines is in the section concerning the severity (and not the diagnosis of) AP. “Laboratory tests may be used as an adjunct to clinical judgment, multiple factors scoring systems, and CT to guide clinical triage decisions. A serum C-reactive protein level > 150 mg/L at 48 hours after disease onset is preferred” (Baillie, 2007).

In 2018, the AGA published guidelines on the initial management of AP. These guidelines state that “the diagnosis of AP requires at least 2 of the following features: characteristic abdominal pain; biochemical evidence of pancreatitis (i.e., amylase or lipase elevated > 3 times the upper limit of normal); and/or radiographic evidence of pancreatitis on cross-sectional imaging” (Crockett et al., 2018).

The AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Epidemiology, Evaluation, and Management of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI) advise that exocrine pancreatic insufficiency “should be suspected in patients with high-risk clinical conditions, such as chronic pancreatitis, relapsing acute pancreatitis, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, cystic fibrosis, and previous pancreatic surgery ... fecal elastase test is the most appropriate initial test and must be performed on a semi-solid or solid stool specimen. A fecal elastase level <100 μg/g of stool provides good evidence of EPI, and levels of 100 – 200 μg/g are indeterminate for EPI” (Whitcomb et al., 2023).

American College of Gastroenterology (ACG)

The ACG released guidelines concerning AP in both 2006 and 2013. Both sets of guidelines recommend the use of the Atlanta classification system regarding the threshold of either serum amylase or serum lipase levels in the diagnosis of AP (i.e., greater than three times the upper limit of normal range). Both sets of guideline’s state that the standard diagnosis is meeting at least two of the three criteria as stated in the revised Atlanta classification system (Banks & Freeman, 2006; Tenner et al., 2013).

The 2006 guidelines discuss the differences between serum amylase and lipase in greater detail. First, although both enzymes can be elevated in AP, the sensitivity and half-life of lipase are more amenable for diagnosis since the levels of lipase remain elevated longer than those of amylase. These guidelines also make note that “it is usually not necessary to measure both serum amylase and lipase” and that “the daily measurement of serum amylase or lipase after the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis has limited value in assessing the clinical progress of the illness”. These guidelines discuss the possibility of elevated amylase levels due to causes other than AP, including but not limited to macroamylasemia, whereas the serum levels of lipase are unaffected by these conditions (Banks & Freeman, 2006).

The 2013 guidelines do not explicitly state a preference of the serum lipase over serum amylase test in the diagnosis of AP. They also state that lipase levels can be elevated in macrolipasemia as well as certain nonpancreatic conditions, “such as renal disease, appendicitis, cholecystitis, and so on”. Neither set of guidelines address the use of either urinary or peritoneal amylase in AP. The 2006 guidelines list other diagnostic tests, including the trypsin/trypsinogen tests as well as serum amyloid A and calcitonin but do not address them further given their limited availability at that time whereas the 2013 guidelines state that, even though other enzymes can be used for diagnostics, “none seems to offer better diagnostic value than those of serum amylase and lipase”. They even state that “even the acute-phase reactant C-reactive protein (CRP) the most widely studied inflammatory marker in AP, is not practical as it takes 72h to become accurate” (Tenner et al., 2013).

American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP) and Choosing Wisely

In 2020, the ASCP, along with Choosing Wisely and the ABIM Foundation, published a brochure titled Thirty Things Physicians and Patients Should Question. This brochure includes the following recommendation:

“Do not test for amylase in cases of suspected acute pancreatitis. Instead, test for lipase.

Amylase and lipase are digestive enzymes normally released from the acinar cells of the exocrine pancreas into the duodenum. Following injury to the pancreas, these enzymes are released into the circulation. While amylase is cleared in the urine, lipase is reabsorbed back into the circulation. In cases of acute pancreatitis, serum activity for both enzymes are greatly increased.

Serum lipase is now the preferred test due to its improved sensitivity, particularly in alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Its prolonged elevation creates a wider diagnostic window than amylase. In acute pancreatitis, amylase can rise rapidly within 3 – 6 hours of the onset of symptoms and may remain elevated for up to five days. Lipase, however, usually peaks at 24 hours with serum concentrations remaining elevated for 8 – 14 days. This means it is far more useful than amylase when the clinical presentation or testing has been delayed for more than 24 hours.

Current guidelines and recommendations indicate that lipase should be preferred over total and pancreatic amylase for the initial diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and that the assessment should not be repeated over time to monitor disease prognosis. Repeat testing should be considered only when the patient has signs and symptoms of persisting pancreatic or peripancreatic inflammation, blockage of the pancreatic duct or development of a pseudocyst. Testing both amylase and lipase is generally discouraged because it increases costs while only marginally improving diagnostic efficiency compared to either marker alone” (ASCP, 2020).

North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Pancreas Committee (NASPGHAN)

The NASPGHAN states that the primary biomarkers used to diagnose AP are serum lipase and amylase and note that “a serum lipase or amylase level of at least 3 times the upper limit of normal is considered consistent with pancreatitis.” Further, NASPGHAN acknowledges that other biomarkers for diagnosis and management of AP have been investigated, but none are prominent and “many have yet to be validated for general clinical use” (NASPGHAN, 2018).

American Psychiatric Association (APA)

The APA published a practice guideline in 2023 for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. In this guideline, pancreatitis (in adults and in adolescents) is just one of a set of factors that supports medical hospitalization or hospitalization on a specialized eating disorder unit.

Also, the APA notes that “serum amylase levels, specifically levels of salivary amylase, may be elevated in patients who self-induce vomiting. With starvation and with renourishment, elevations in serum lipase can be seen but generally do not require intervention” (APA, 2023).

Academy for Eating Disorders (AED) Medical Care Standards Committee

The AED has published a guide to medical care for eating disorders. A table is included in these guidelines which is titled Diagnostic Tests Indicated for All Patients with A Suspected ED [eating disorder]. In a subcategory, titled Criteria Supportive of Hospitalization for Acute Medical Stabilization, these guidelines mention that “acute medical complications of malnutrition” including pancreatitis may occur (AED, 2021).

The American Association for Clinical Chemistry

The American Association for Clinical Chemistry released recommendations for amylase testing in diagnosis and management of acute pancreatitis. The AACC provides the following recommendations:

- “For diagnosis and management of acute pancreatitis, do not order this test if serum lipase test is available.

- May be considered for the diagnosis and monitoring of chronic pancreatitis and other pancreatic diseases.”

The AACC does mention that “the test is not specific for pancreatitis and may be elevated due to other, non-pancreatic causes (such as acute cholecystitis, inflammatory bowel disease, intestinal obstruction, certain cancers, salivary disease, macroamylasemia, etc.)”.

- The AACC further states to “consider ordering this test when serum lipase is not available as a stat test and the patient presents with a sudden onset of abdominal pain with nausea and vomiting, fever, hypotension, and abdominal distension ”and that “testing both amylase and lipase should be discouraged because it increases costs while only marginally improving diagnostic efficiency compared to lipase alone” (AACC, 2023).

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH)

The CADTH has published an advisory panel guidance on minimum retesting intervals for lab tests. They identify the following key issues:

- “Lab test overuse can contribute to further unnecessary follow-up and testing, negative patient experiences, potentially inappropriate treatments, and the inefficient use of health care resources. One review of lab testing in Canada found that around 22% of blood tests were likely unnecessary.

- One strategy to address lab test overuse is to establish minimal retesting intervals that can be implemented in medical laboratories to help identify and manage potentially inappropriate lab test requests.

- Minimum retesting intervals suggest the minimum time before a test should be repeated based on the biochemical properties of the test and the clinical situation in which it is used. They are intended to inform clinical decisions about repeat testing” (CADTH, 2024).

Specific to repeat lipase testing, they do not recommend reordering lipase tests:

- “Do not reorder lipase tests for monitoring patients with an established diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.

- Do not reorder lipase tests for monitoring patients with an established diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. An exception to this recommendation is if there is clinical suspicion of acute-on-chronic pancreatitis, where lipase testing is required for diagnostic purposes” (CADTH, 2024).

Implementation advise for this recommendation: “To support reductions in unnecessary retesting, in outpatient or community settings, labs may consider implementing a 6-month hard stop minimum retesting interval.

This recommendation is based on the experience of the advisory panel as no relevant information for serum lipase retesting for chronic pancreatitis was identified in the literature review” (CADTH, 2024).

References

- AACC. (2023). AACC's Guide to Lab Test Utilization https://www.aacc.org/advocacy-and-outreach/optimal-testing-guide-to-lab-test-utilization/a-f/amylase

- AED. (2021). EATING DISORDERS A GUIDE TO MEDICAL CARE. Academy for Eating Disorders, 1-26. https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/AEDWEB/27a3b69a-8aae-45b2-a04c-2a078d02145d/UploadedImages/Publications_Slider/2120_AED_Medical_Care_4th_Ed_FINAL.pdf

- APA. (2023). The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders. The American Psychiatric Association https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890424865

- ASCP. (2020). Thirty Things Physicians and Patients Should Question. https://www.ascp.org/content/docs/default-source/get-involved-pdfs/istp_choosingwisely/2019_ascp-30-things-list.pdf

- Baillie, J. (2007). AGA Institute Medical Position Statement on Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology, 132(5), 2019-2021. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.066

- Banks, P., & Freeman, M. (2006). Practice Guidelines in Acute Pancreatitis [Practice Guideline]. The American Journal Of Gastroenterology, 101, 2379. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00856.x

- Banks, P. A., Bollen, T. L., Dervenis, C., Gooszen, H. G., Johnson, C. D., Sarr, M. G., Tsiotos, G. G., & Vege, S. S. (2013). Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut, 62, 102-111. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779

- Barry, K. (2018). Chronic Pancreatitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. American Academy of Family Physician, Volume 97. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2018/0315/p385.html#:~:text=If%20chronic%20pancreatitis%20is%20suspected,best%20imaging%20modality%20for%20diagnosis.

- Basnayake, C., & Ratnam, D. (2015). Blood tests for acute pancreatitis. Australian Prescriber, 38(4), 128-130. https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2015.043

- Bollen, T. L., Hazewinkel, M., & Smithuis, R. (2015, 05/01/2015). Acute Pancreatitis 2012 Revised Atlanta Classification of Acute Pancreatitis. Radiology Society of the Netherlands. Retrieved 05/22/2018 from https://radiologyassistant.nl/abdomen/pancreas/acute-pancreatitis

- Borowitz, D., Grant, R., & Durie, P. (1995, 2016). Pancreatic Enzymes Clinical Care Guidelines. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Retrieved 5/17/2018 from https://www.cff.org/Care/Clinical-Care-Guidelines/Nutrition-and-GI-Clinical-Care-Guidelines/Pancreatic-Enzymes-Clinical-Care-Guidelines/

- Bradley, E. (1993). A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis: Summary of the international symposium on acute pancreatitis, atlanta, ga, september 11 through 13, 1992. Archives of Surgery, 128(5), 586-590. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420170122019

- Burkart, J., Haigler, S., Caruana, R., & Hylander, B. (1991). Usefulness of peritoneal fluid amylase levels in the differential diagnosis of peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol, 1(10), 1186-1190. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.v1101186

- CADTH. (2024). In Advisory Panel Guidance on Minimum Retesting Intervals for Lab Tests: Appropriate Use Recommendation. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39088670

- Ceylan, M. E., Evrensel, A., & Önen Ünsalver, B. (2016). Hyperamylasemia Related to Sertraline. Korean Journal of Family Medicine, 37(4), 259-259. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.2016.37.4.259

- Clavien, P. A., Robert, J., Meyer, P., Borst, F., Hauser, H., Herrmann, F., Dunand, V., & Rohner, A. (1989). Acute pancreatitis and normoamylasemia. Not an uncommon combination. Ann Surg, 210(5), 614-620. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-198911000-00008

- Coffey, M. J., Nightingale, S., & Ooi, C. Y. (2013). Serum Lipase as an Early Predictor of Severity in Pediatric Acute Pancreatitis. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 56(6), 602-608. https://doi.org/10.1097/mpg.0b013e31828b36d8

- Crockett, S. D., Wani, S., Gardner, T. B., Falck-Ytter, Y., & Barkun, A. N. (2018). American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on Initial Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology, 154(4), 1096-1101. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.032

- Eastler, J. (2023, 08/14/2017). Urine Trypsinogen 2 Dipstick for the Early Detection of Post-ERCP Pancreatitis. National Library of Medicine-National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 05/17/2018 from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT03098082?view=record

- El Halabi, M., Bou Daher, H., Rustom, L. B. O., Marrache, M., Ichkhanian, Y., Kahil, K., El Sayed, M., & Sharara, A. I. (2019). Clinical utility and economic burden of routine serum lipase determination in the Emergency Department. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 73(12), e13409. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13409

- Freedman, S. D., & Forsmark, C. E. (2024). Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis in adults. Wolters Kluwer. Retrieved 05/29/2018 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-chronic-pancreatitis-in-adults

- Furey, C., Buxbaum, J., & Chambliss, A. B. (2020). A review of biomarker utilization in the diagnosis and management of acute pancreatitis reveals amylase ordering is favored in patients requiring laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clin Biochem, 77, 54-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2019.12.014

- Gapp, J., Tariq, A., & Chandra, S. (2023). Acute Pancreatitis. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482468/

- Gumaste, V. V., Dave, P. B., Weissman, D., & Messer, J. (1991). Lipase/amylase ratio. A new index that distinguishes acute episodes of alcoholic from nonalcoholic acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology, 101(5), 1361-1366. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(91)90089-4

- Hagjer, S., & Kumar, N. (2018). Evaluation of the BISAP scoring system in prognostication of acute pancreatitis - A prospective observational study. Int J Surg, 54(Pt A), 76-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.04.026

- Herrmann-Storck, C., Saint Louis, M., Foucand, T., Lamaury, I., Deloumeaux, J., Baranton, G., Simonetti, M., Sertour, N., Nicolas, M., Salin, J., & Cornet, M. (2010). Severe Leptospirosis in Hospitalized Patients, Guadeloupe. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 16(2), 331-334. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1602.090139

- IAP/APA Working Group. (2013). IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology, 13(4), e1-e15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pan.2013.07.063

- informedhealth.org. (2021, 05/25/2021). Acute pancreatitis: Learn More – How is acute pancreatitis treated? https://www.informedhealth.org/acute-pancreatitis.html

- Ismail, O. Z., & Bhayana, V. (2017). Lipase or amylase for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis? Clin Biochem, 50(18), 1275-1280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.07.003

- Jakkampudi, A., Jangala, R., Reddy, R., Mitnala, S., Rao, G. V., Pradeep, R., Reddy, D. N., & Talukdar, R. (2017). Acinar injury and early cytokine response in human acute biliary pancreatitis. Sci Rep, 7(1), 15276. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15479-2

- Judal, H., Ganatra, V., & Choudhary, P. R. (2022). Urinary amylase levels in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis: a prospective case control study. International Surgery Journal, 9(2), 432-437. https://doi.org/10.18203/2349-2902.isj20220337

- Kemppainen, E. A., Hedstrom, J. I., Puolakkainen, P. A., Sainio, V. S., Haapiainen, R. K., Perhoniemi, V., Osman, S., Kivilaakso, E. O., & Stenman, U. H. (1997). Rapid measurement of urinary trypsinogen-2 as a screening test for acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med, 336(25), 1788-1793. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199706193362504

- Khanna, A. K., Meher, S., Prakash, S., Tiwary, S. K., Singh, U., Srivastava, A., & Dixit, V. K. (2013). Comparison of Ranson, Glasgow, MOSS, SIRS, BISAP, APACHE-II, CTSI Scores, IL-6, CRP, and Procalcitonin in Predicting Severity, Organ Failure, Pancreatic Necrosis, and Mortality in Acute Pancreatitis. HPB Surgery, 2013, 367581. https://doi.org/10.1155%2F2013%2F367581

- Klochkov, A. K., Pujuitha, Lim, Y., & Sun, Y. (2023). Alcoholic Pancreatitis. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537191/#:~:text=Chronic%20alcohol%20consumption%20is%20the,developing%20pancreatic%20cancer%20%5B5%5D.

- Kumar, P., Ghosh, A., Tandon, V., & Sahoo, R. (2016). Gullo’s Syndrome: A Case Report. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research : JCDR, 10(2), OD21-OD22. https://doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2016/17038.7285

- Lempinen, M., Kylänpää-Bäck, M.-L., Stenman, U.-H., Puolakkainen, P., Haapiainen, R., Finne, P., Korvuo, A., & Kemppainen, E. (2001). Predicting the Severity of Acute Pancreatitis by Rapid Measurement of Trypsinogen-2 in Urine. Clinical Chemistry, 47(12), 2103. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/47.12.2103

- Levy, P., Boruchowicz, A., Hastier, P., Pariente, A., Thevenot, T., Frossard, J. L., Buscail, L., Mauvais, F., Duchmann, J. C., Courrier, A., Bulois, P., Gineston, J. L., Barthet, M., Licht, H., O'Toole, D., & Ruszniewski, P. (2005). Diagnostic criteria in predicting a biliary origin of acute pancreatitis in the era of endoscopic ultrasound: multicentre prospective evaluation of 213 patients. Pancreatology, 5(4-5), 450-456. https://doi.org/10.1159/000086547

- Li, N., Wang, B. M., Cai, S., & Liu, P. L. (2018). The Role of Serum High Mobility Group Box 1 and Interleukin-6 Levels in Acute Pancreatitis: A Meta-Analysis. J Cell Biochem, 119(1), 616-624. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.26222

- Lippi, G., Valentino, M., & Cervellin, G. (2012). Laboratory diagnosis of acute pancreatitis: in search of the Holy Grail. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences, 49(1), 18-31. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408363.2012.658354

- Liu, P., Xiao, Z., Yan, H., Lu, X., Zhang, X., Luo, L., Long, C., & Zhu, Y. (2021). Serum Amylase and Lipase for the Prediction of Pancreatic Injury in Critically Ill Children Admitted to the PICU. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 22(1), e10-e18. https://doi.org/10.1097/pcc.0000000000002525

- Liu, S., Wang, Q., Zhou, R., Li, C., Hu, D., Xue, W., Wu, T., Mohan, C., & Peng, A. (2016). Hyperamylasemia as an Early Predictor of Mortality in Patients with Acute Paraquat Poisoning. Medical Science Monitor : International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, 22, 1342-1348. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.897930

- NASPGHAN. (2018). Management of Acute Pancreatitis in the Pediatric Population: A Clinical Report From the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Pancreas Committee. https://www.naspghan.org/files/Management_of_Acute_Pancreatitis_in_the_Pediatric.33.pdf

- Neoptolemos, J. P., Kemppainen, E. A., Mayer, J. M., Fitzpatrick, J. M., Raraty, M. G., Slavin, J., Beger, H. G., Hietaranta, A. J., & Puolakkainen, P. A. (2000). Early prediction of severity in acute pancreatitis by urinary trypsinogen activation peptide: a multicentre study. Lancet, 355(9219), 1955-1960. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02327-8

- NIDDK. (2017, 11/2017). Symptoms & Causes of Pancreatitis. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/pancreatitis/symptoms-causes

- Pacheco, R. C., & Oliveira, L. C. (2007). [Lipase/amylase ratio in biliary acute pancreatitis and alcoholic acute/acutized chronic pancreatitis]. Arq Gastroenterol, 44(1), 35-38. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0004-28032007000100008 (Relacao lipase/amilase nas pancreatites agudas de causa biliar e nas pancreatites agudas/cronicas agudizadas de causa alcoolica.)

- Patel, J., Madan, A., Gammon, A., Sossenheimer, M., Samadder, N. J. (2017). Rare hereditary cause of chronic pancreatitis in a young male: SPINK1 mutation. The Pan African medical journal, 28, 110. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2017.28.110.13854

- Pezzilli, R., Venturi, M., Morselli-Labate, A. M., Ceciliato, R., Lamparelli, M. G., Rossi, A., Moneta, D., Piscitelli, L., & Corinaldesi, R. (2004). Serum Trypsinogen Activation Peptide in the Assessment of the Diagnosis and Severity of Acute Pancreatic Damage: A Pilot Study Using a New Determination Technique. Pancreas, 29(4), 298-305. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006676-200411000-00009

- Quinlan, J. D. (2014). Acute pancreatitis. Am Fam Physician, 90(9), 632-639. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/1101/p632.html

- Rau, B. M., Kemppainen, E. A., Gumbs, A. A., Buchler, M. W., Wegscheider, K., Bassi, C., Puolakkainen, P. A., & Beger, H. G. (2007). Early assessment of pancreatic infections and overall prognosis in severe acute pancreatitis by procalcitonin (PCT): a prospective international multicenter study. Ann Surg, 245(5), 745-754. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000252443.22360.46

- Ritter. J, Ghirimoldi. F, Manuel. L, Moffett. E, Novicki. T, McClay. J, Shireman. P, & B, B. (2019). Cost of Unnecessary Amylase and Lipase Testing at Multiple Academic Health Systems. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqz170

- Rompianesi, G., Hann, A., Komolafe, O., Pereira, S. P., Davidson, B. R., & Gurusamy, K. S. (2017). Serum amylase and lipase and urinary trypsinogen and amylase for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd012010.pub2

- Ryholt, V., Soder, J., Enderle, J., & Rajendran, R. (2024). Assessment of appropriate use of amylase and lipase testing in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis at an academic teaching hospital. Lab Med. https://doi.org/10.1093/labmed/lmae008

- Sendler, M., & Lerch, M. M. (2020). The Complex Role of Trypsin in Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology, 158(4), 822-826. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.025

- Simha, A., Saroch, A., Pannu, A. K., Dhibar, D. P., Sharma, N., Singh, H., & Sharma, V. (2021). Utility of point-of-care urine trypsinogen dipstick test for diagnosing acute pancreatitis in an emergency unit. Biomarkers in Medicine, 15(14), 1271-1276. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm-2021-0067

- Simsek, O., Kocael, A., Kocael, P., Orhan, A., Cengiz, M., Balci, H., Ulualp, K., & Uzun, H. (2018). Inflammatory mediators in the diagnosis and treatment of acute pancreatitis: pentraxin-3, procalcitonin and myeloperoxidase. Arch Med Sci, 14(2), 288-296. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2016.57886

- Stevens, T., & Conwell, D. L. (2024, 10/05/2016). Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Retrieved 05/18/2018 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/exocrine-pancreatic-insufficiency

- Tenner, S., Baillie, J., DeWitt, J., & Vege, S. S. (2013). American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol, 108(9), 1400-1415; 1416. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2013.218

- Tenner, S. M., & Steinberg, W. (1992). The admission serum lipase:amylase ratio differentiates alcoholic from nonalcoholic acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol, 87(12), 1755-1758. https://europepmc.org/article/MED/1280405

- Terui, K., Hishiki, T., Saito, T., Mitsunaga, T., Nakata, M., & Yoshida, H. (2013). Urinary amylase / urinary creatinine ratio (uAm/uCr) - a less-invasive parameter for management of hyperamylasemia. BMC Pediatrics, 13, 205-205. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-13-205

- Tian, F., Li, H., Wang, L., Li, B., Aibibula, M., Zhao, H., Feng, N., Lv, J., Zhang, G., & Ma, X. (2020). The diagnostic value of serum C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, interleukin-6 and lactate dehydrogenase in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Clinica Chimica Acta, 510, 665-670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.08.029

- Toouli, J., Brooke-Smith, M., Bassi, C., Carr-Locke, D., Telford, J., Freeny, P., Imrie, C., & Tandon, R. (2002). Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 17 Suppl, S15-39. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1746.17.s1.2.x

- Vege, S. S. (2024a, 05/21/2018). Approach to the patient with elevated serum amylase or lipase. Wolters Kluwer. Retrieved 05/23/2018 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-elevated-serum-amylase-or-lipase

- Vege, S. S. (2024b). Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Wolters Kluwer. Retrieved 05/23/2018 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-acute-pancreatitis

- Vege, S. S. (2024c, 02/24/2017). Pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Wolters Kluwer. Retrieved 05/23/2018 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pathogenesis-of-acute-pancreatitis

- Ventrucci, M., Pezzilli, R., Naldoni, P., Plate, L., Baldoni, F., Gullo, L., & Barbara, L. (1987). Serum pancreatic enzyme behavior during the course of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas, 2(5), 506-509. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006676-198709000-00003

- Wei, M., Xie, X., Yu, X., Lu, Y., Ke, L., Ye, B., Zhou, J., Li, G., Li, B., Tong, Z., Lu, G., Li, W., & Li, J. (2022). Predictive value of serum cholinesterase in the mortality of acute pancreatitis: A retrospective cohort study. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, n/a(n/a), e13741. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13741

- Whitcomb, D. C., Buchner, A. M., & Forsmark, C. E. (2023). AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Epidemiology, Evaluation, and Management of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency: Expert Review. Gastroenterology, 165(5), 1292-1301. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.007

- Witt, H., Apte, M. V., Keim, V., & Wilson, J. S. (2007). Chronic pancreatitis: challenges and advances in pathogenesis, genetics, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterology, 132(4), 1557-1573. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.001

- Wolfe, B. E., Jimerson, D. C., Smith, A., & Keel, P. K. (2011). Serum Amylase in Bulimia Nervosa and Purging Disorder: Differentiating the Association with Binge Eating versus Purging Behavior. Physiology & behavior, 104(5), 684-686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.06.025

- Yadav, D., Agarwal, N., & Pitchumoni, C. S. (2002). A critical evaluation of laboratory tests in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol, 97(6), 1309-1318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05766.x

- Yang, H., Wang, H., Chavan, S. S., & Andersson, U. (2015). High Mobility Group Box Protein 1 (HMGB1): The Prototypical Endogenous Danger Molecule. Mol Med, 21 Suppl 1, S6-s12. https://doi.org/10.2119%2Fmolmed.2015.00087

- Yasuda, H., Kataoka, K., Takeyama, Y., Takeda, K., Ito, T., Mayumi, T., Isaji, S., Mine, T., Kitagawa, M., Kiriyama, S., Sakagami, J., Masamune, A., Inui, K., Hirano, K., Akashi, R., Yokoe, M., Sogame, Y., Okazaki, K., Morioka, C., . . . Shimosegawa, T. (2019). Usefulness of urinary trypsinogen-2 and trypsinogen activation peptide in acute pancreatitis: A multicenter study in Japan. World J Gastroenterol, 25(1), 107-117. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i1.107

- Zhan, X., Wan, J., Zhang, G., Song, L., Gui, F., Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Guo, J., Dawra, R. K., Saluja, A. K., Haddock, A. N., Zhang, L., Bi, Y., & Ji, B. (2019). Elevated intracellular trypsin exacerbates acute pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis in mice. Am J Physiol GastrointestLiver Physiol, 316(6), G816-g825. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00004.2019

Coding Section

| Code | Number | Description |

| CPT | 82150 | Amylase |

| 83519 | Immunoassay for analyte other than infectious agent antibody or infectious agent antigen; quantitative, by radioimmunoassay (e.g., RIA | |

| 83520 | Immunoassay for analyte other than infectious agent antibody or infectious agent antigen; quantitative, not otherwise specified | |

| 83529 (effective 01/01/2022) | Interleukin-6 | |

| 83690 | Lipase | |

| 84145 | Procalcitonin (PCT) | |

| 86140 | C-reactive protein | |

| ICD-10 Diagnoses Codes | F50.00-F50.9 | Anorexia nervosa |

| K56.0, K56.3, K56.7 | Ileus | |

| K85.00-K85.92 | Acute pancreatitis | |

| K86.0 and K86.1 | Chronic Pancreatitis | |

| M79.3 | Panniculitis, unspecified | |

| M79.89 | Subcutaneous nodular fat necrosis | |

| R00.0 | Tachycardia | |

| R03.1 | Nonspecific low blood-pressure reading | |

| R06.02 | shortness of breath | |

| R06.82 | Tachypnea, not elsewhere classified | |

| R07.1 | Chest pain on breathing/Painful respiration | |

| R09.02 | Hypoxemia | |

| R10.10, R10.11 and R10.12 | Upper abdominal pain | |

| R10.13 | Epigastric pain | |

| R10.811 – R10.819 | Tenderness when touching the abdomen | |

| R10.84 | Abdominal pain that feels worse after eating | |

| R10.9 | Abdominal pain that radiates to your back | |

| R11.0 | Nausea | |

| R11.10, R11.11 | Vomiting | |

| R11.2 | Nausea with vomiting, unspecified | |

| R14.0 | Abdominal distention | |

| R17 | Unspecified jaundice | |

| R19.00 - R19.09 | Abdominal swelling | |

| R19.11 | Absent bowel sounds | |

| R19.15 | Other abnormal bowel sounds | |

| R50.9 | Fever, fever of chills, elevated body temp | |

| R61 | Generalized hyperhidrosis | |

| R63.0 | Anorexia | |

| R74.8 | Abnormal levels of other serum enzymes | |

| S39.81XA-S39.81XS | Other specified injuries of abdomen | |

| S39.91XA-S39.91XS | Unspecified injury of abdomen | |

| S30.1XXA-S30.1XXS | Contusion of abdominal wall, Flank ecchymosis, Periumbilical ecchymosis |

Procedure and diagnosis codes on Medical Policy documents are included only as a general reference tool for each policy. They may not be all-inclusive.

This medical policy was developed through consideration of peer-reviewed medical literature generally recognized by the relevant medical community, U.S. FDA approval status, nationally accepted standards of medical practice and accepted standards of medical practice in this community, and other nonaffiliated technology evaluation centers, reference to federal regulations, other plan medical policies, and accredited national guidelines.

"Current Procedural Terminology © American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved"

History From 2018 Forward

| 10/11/2024 | Annual review, policy being updated for clarity and consistency. Criteria #6 addresses all issues not covered din the first 5 criteria as being not medically necessary. Also updating Note 1, rationale and references, and table of terminology. |

| 07/29/2024 | Change review date to 10/01/2024. |

| 07/11/2023 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updating policy for clarity and consistency. Also updating notes, description, table of terminology, rational and references. |